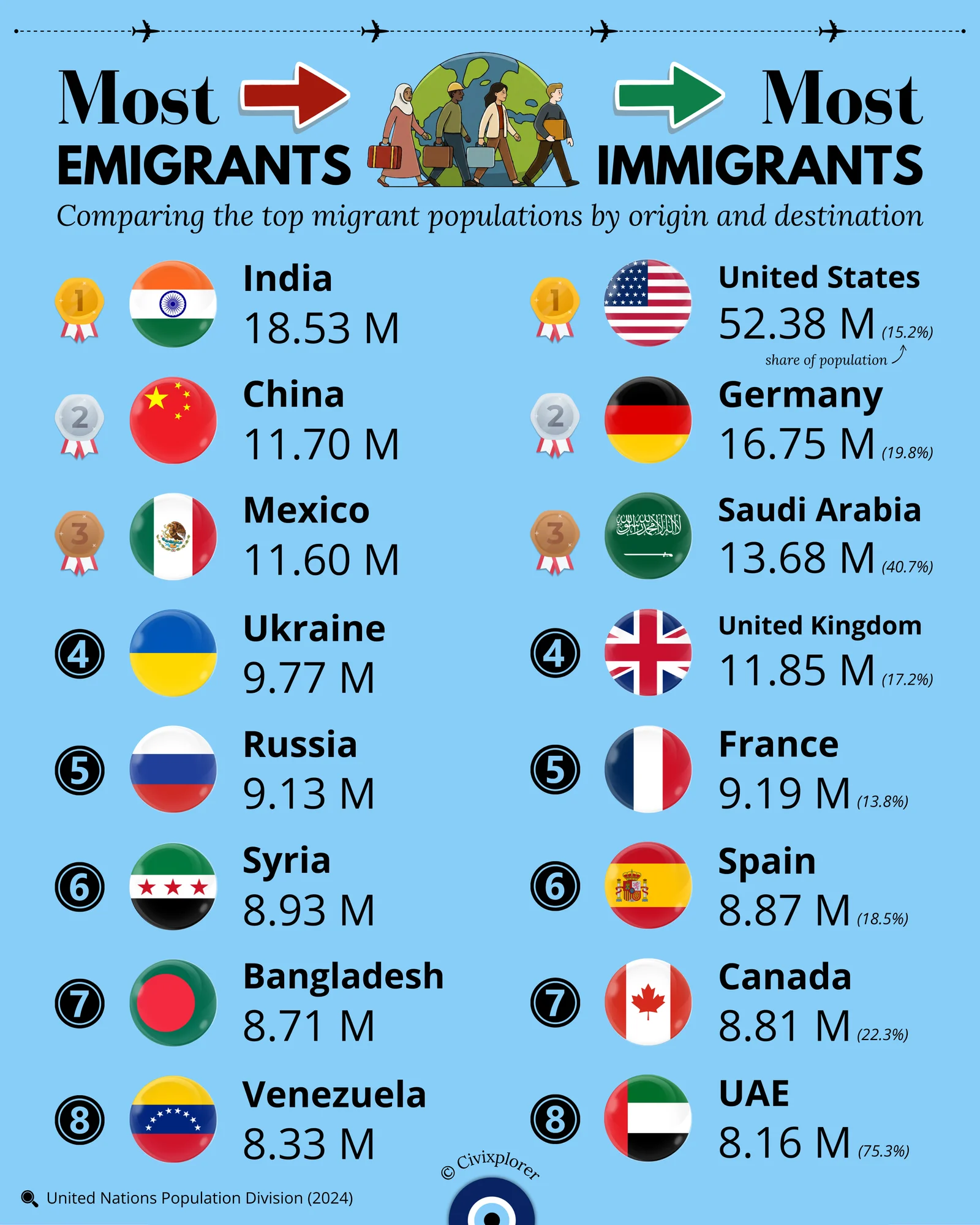

The 21st century is defined by profound demographic shifts that are reshaping the global landscape. While international migration has reached a record high of approximately 304 million people, this group still represents a relatively small fraction—about 3.7%—of the total global population. The data illustrates a world increasingly divided by "push" and "pull" factors, creating specific clusters of movement that mirror global economic and political realities.

The Middle East has emerged as a primary "Oil and Labor" magnet, with countries like the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia showing extraordinary shares of immigrant populations, sometimes exceeding 80%. This is largely due to the Rentier State model, where nations with vast oil wealth but small native populations require massive external workforces to build infrastructure and maintain service economies. Much of this is managed through the Kafala sponsorship system, which facilitates high volumes of temporary labor, though it often leaves workers vulnerable. In these regions, a distinct sectoral segregation exists: immigrants perform the majority of manual and private-sector labor, while citizens typically hold government positions.

In Western nations such as the United States, Germany, Canada, and Spain, immigration is increasingly driven by structural necessity. Many of these countries are facing a demographic crisis characterized by aging populations and low birth rates; without a steady flow of immigrants, their labor forces would shrink and social security systems could face collapse. Beyond wages, the "pull" of the West is often the "institutional quality"—the promise of safety, rule of law, and better education for the next generation. Historical and linguistic ties also play a major role, dictating traditional corridors such as migration from Latin America to Spain or the USA.

Conversely, emigration is rarely a choice of luxury and is often a response to structural ceilings or survival needs. While conflict and repression in nations like Ukraine, Syria, and Sudan cause "forced displacement," other economic phenomena are at play elsewhere. For instance, the "Migration Hump" theory suggests that as a country moves from low to middle income, emigration actually increases because citizens finally gain the resources needed to move in search of higher gains. In cases like Venezuela, total systemic failure a

Comments (0)

Join the Conversation

Login to share your thoughts with the community.

Login to Comment