The visual journey of Buddhist iconography is a masterclass in cultural adaptation and artistic fusion. For nearly two millennia, the portrayal of the Buddha evolved from its South Asian roots into a kaleidoscope of regional styles, reflecting the unique ethnicities and traditions of the Silk Road and beyond.

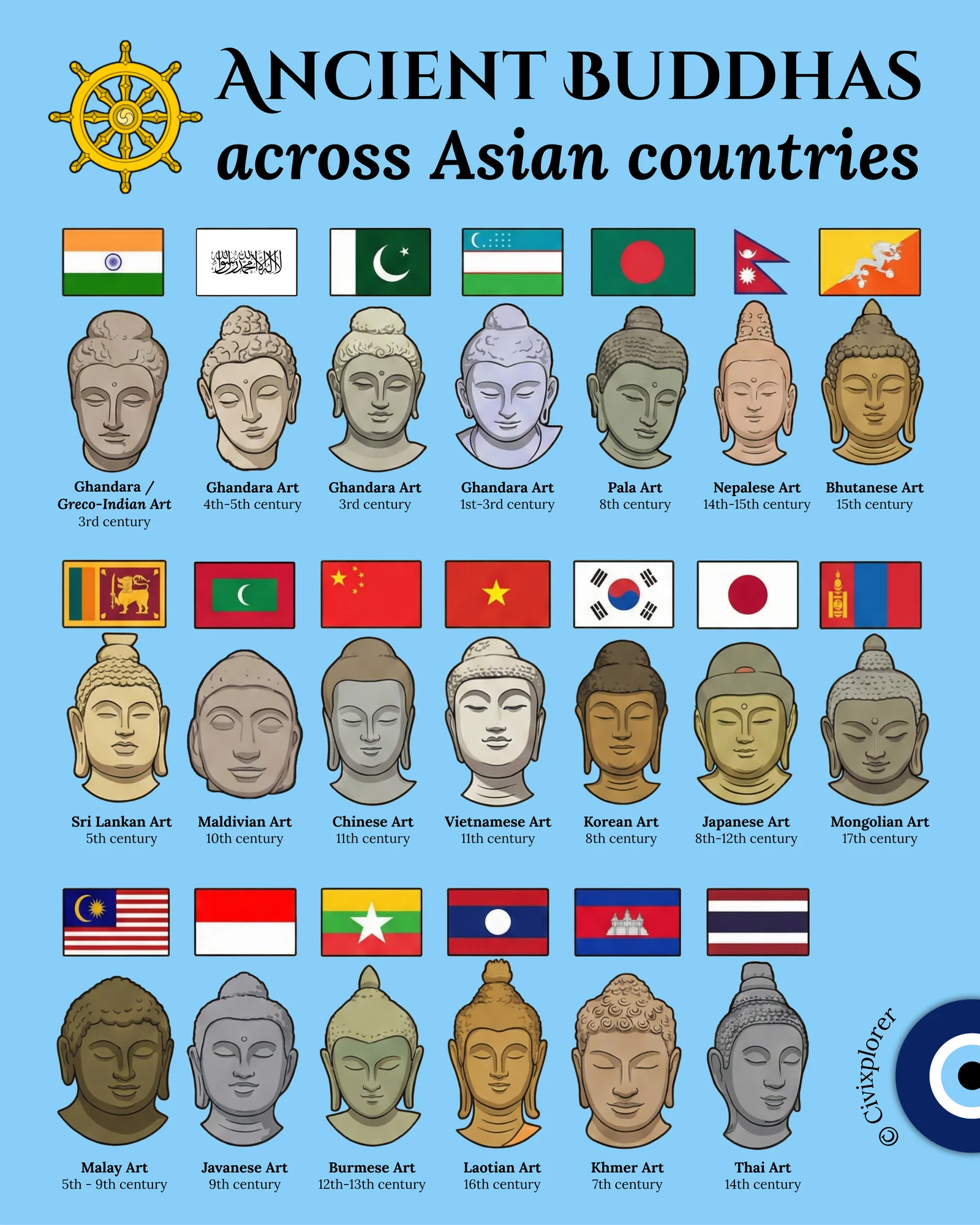

The story begins with the Greco-Indian Gandhara art found in modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan between the 1st and 5th centuries. Influenced by the conquests of Alexander the Great, these early depictions merged Greek artistic techniques with Indian spirituality. This resulted in Buddhas with distinct Hellenistic features, such as wavy hair and facial structures reminiscent of the Greek god Apollo.

As Buddhism traveled east into China, Korea, and Japan, a process of localization took hold. Artists began to reflect their own populations in their work, introducing features such as almond-shaped eyes and more rounded jawlines. During this era, the Buddha’s expression shifted toward an idealized serenity, emphasizing a meditative and introspective state characterized by geometric hair curls and elongated earlobes.

A defining feature across these diverse styles is the "Usnisha," the cranial protrusion symbolizing enlightenment. While often mistaken for a hair bun, its form varies significantly by region. In Thailand and Laos, the Usnisha frequently appears as a sharp, flame-like point representing spiritual energy, whereas East Asian Zen or Mahayana traditions typically favor a flatter, more subtle bump.

In Southeast Asia, powerful empires like the Khmer and the Majapahit left their own indelible marks. The "Smile of Angkor" in 7th-century Khmer art features thick lips and a mysterious grin intended to convey supreme inner peace. Meanwhile, 9th-century Javanese art reflected the era of Borobudur, blending Indian influences with local facial structures to create a sense of sturdy, meditative realism.

Ultimately, these artistic variations prove that Buddhism was a philosophical export rather than a colonizing force. Local rulers and artists adopted the Buddha’s image to make the faith relatable to their people, ensuring that the divine was always reflected through a local lens.

Comments (0)

Join the Conversation

Login to share your thoughts with the community.

Login to Comment